Nikolas Wereszczynski: ‘Printmaking is a very physical process – the calluses make it inch ever closer to being a folk craft’

- lucy w

- Mar 29, 2024

- 5 min read

Nikolas draws inspiration from folk culture, animism and the tactile act of making something with your hands. He explains how he became a printmaker – despite not liking it at secondary school – and his exploration of different techniques and styles.

How did you get into printmaking?

I got into printmaking through lino – I don’t remember exactly who or what it was at the time that inspired me enough to push me over the edge of actually getting my hands on it, but at a certain point I was seeing more and more black and white linocuts that were visually very strong and expressive. I thought they had a strong graphic quality to them and that the style of linocut as a medium lent itself to being very folk-like too, which appealed to me. I gave it a go and the rest is history!

It definitely helped for linocut to be a form of printmaking that doesn’t require a press or a studio, so I could work on it whenever I wanted from the comfort of my home.

Funnily enough though, I was first exposed to lino back in secondary school, but didn’t like it at all! We were making Pop Art-style work, and while I see why a teacher would think it was a great way to introduce children to this medium, I just didn’t like it at all and so never thought I’d return to it.

Folk culture plays a big part in your work. Why is this a favourite subject for you?

This is probably the most complex question about my work that I get asked, and I still have trouble explaining it in a way that I feel is coherent enough! To me, folk culture is deeply animistic and I truly believe that traces of animistic beliefs have survived in the form of folk culture, especially in places that have been colonised by now-dominant religions.

One of the reasons why this has become so important to me is my exploration of my own culture.

In Polish schools or history books, the country’s history unfortunately tends to begin in the year 966 – the year that Poland was baptised and Christianity became the state religion. But what were people’s beliefs before that? Why is there so little interest in them? The folk culture of Poland that we are so proud of and that is so widely celebrated has origins in periods way before that time.

So one of the reasons for my interest has its roots in wanting to find out more about the beliefs, traditions and culture of people as far back as I can get. In fact, my favourite period of looking at religious rites and related artefacts is the Stone Age, before social stratification, but that’s a whole other kettle of fish!

As to why I am interested in folk culture in the first place, I think goes back to this relation to animism and my own beliefs.

I think both folk culture and animism essentially deify the flesh, as well as the daily life we live and everything we do to sustain it – hunting and collecting food, cooking it, making vessels to cook that food in, making clothes for both protection and adornment, recognising and venerating the very real movement and the aliveness of everything around us.

All these things are inseparable both from animism and the development of folk traditions and have constantly affected each other.

Those things are sacred because they are an inseparable part of us, they are synonymous with life and the world. Folk culture and animism don’t just recognise the effect of everything on human life, but in fact completely erase the distinction between “us” and “it”, between “inside” and “outside”, “sacred” and “mundane”.

So in short, my artwork is essentially an exploration of folk culture and beliefs, but also an expression of my own religious ones.

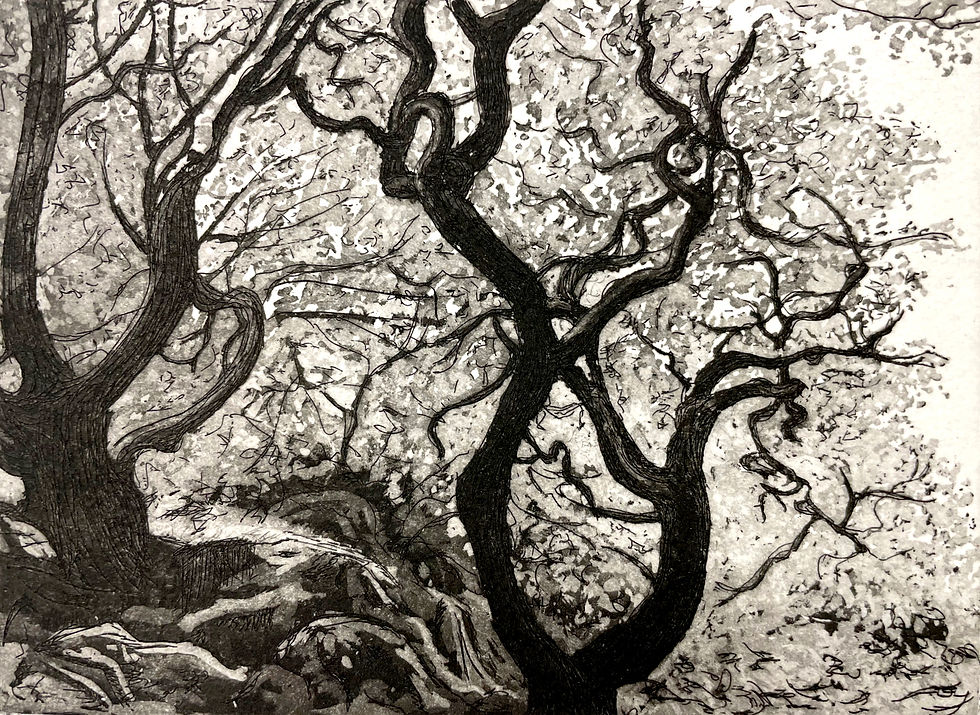

You have a great use of line in your work, from some of your very minimalist prints of oysters to more graphic linocuts and drypoints such as “Turoń”. Where does that come from?

Before starting my journey as a printmaker, I was (and still am!) a highly illustrative painter – everything I do starts from a sketch, especially if I’m working on a piece that is very detailed or just needs to be carefully planned out. It’s very rewarding to end up with a sketch you like, but at the same time it’s also the most stressful step of creating an artwork for me – it’s the basis, the skeleton of the work, and everything has to be just right (especially the composition which I get way too obsessive about), so I tend to stress about it and can’t move on until I’m 100% satisfied.

But the most recent development in my art practice is to try to be more spontaneous and experimental, which is how “Oyster” and similar pieces have come about. I’ve started drawing quick, continuous-line sketches straight onto lino and carving out the ones I like to turn into final prints. It’s an exercise in being more intuitive.

You mentioned that you’re in the process of learning mokuhanga (Japanese woodblock printing). What made you want to explore this technique?

Part of it was definitely related to my longstanding interest in Japanese crafts and Japanese culture as a whole, but I also really like wood and natural materials. I remember thinking how much I would like to try to work with wood in printmaking, and also thinking about it in a very tactile way – thinking about the way the wood would feel in my hands, how it smells and how it feels to tire out the skin on your hands after a couple of hours of intense work. I’ve done some whittling with wood on a few occasions and so I was very familiar with the sensations.

This is probably one of the reasons why I really enjoy the printmaking process too – even though the final piece is 2D, you're working into a 3D material; it’s a very tactile, physical process and it feels really good to get your hands dirty, to get calluses after long hours of work, and to even occasionally injure yourself and spill blood for the process.

It makes the medium of printmaking something so much more physical, and it makes it inch ever closer to being a folk craft.

Another thing that I really love about mokuhanga is that it lends itself much better to colour than linocut, in my opinion. You’re working with water-based paints so you can get some really nice, gentle gradients in alongside strong colours. It’s very similar to the way I paint and I’ve started saying that mokuhanga printing feels much more like making multiple copies of a painting than a print in that way.

Nikolas’s prints are available in the Greenwich Printmakers gallery and in our online shop. For more information, visit his artist’s page and his website.

Comments